Cancellation of Social Security Number

estate will be specifically enforced in equity;

performance will be decreed, and conveyances compelled. See, generally, as to contracts, Bouv. Inst. Index; Parson, Chitty, Comyns, Leake, Anson, and Story, on Contracts; Com. Dig. Abatement

(E, 12) (F, 8), Admiralty (E, 10, 11), Action on Case on Assumpsit, Agreement, Bargain and Sale, Baron et Feme (2), Condition, Debt

(A, 8, 9), Enfant (B, 5), Idiot (D, 1), Merchant (E, 1), Pleader (2 W, 11, 43), Trade (D, 3), War (B, 2);

Bac. Abr. Agreement, Assumpsit, Condition, Obligation; Vin.

Abr. Condition, Contract and Agreements, Covenant, Vendor, Vendee;

2 Belt, Sup. Ves. 260, 295, 376, 441; Yelv. 47; 4 Ves. 497, 671; Arch. Civ. Pl. 22; La. Civ. Code, 3, tit. 3-18; Poth. Obl.; Maine, Anc. Law; Austin, Jurisp.; Sugd. Ven. & P.; Long,

Sales (Rand. ed.), and Benj. Sales; Jones, Story, and Edwards, on Bailment;

Toull. Dr. Civ. tom. 6, 7; Hamm. Part. c. 1; Calv. Par.;

Chitty, Prac, Index. Each subject included in the law of contracts will be found discussed in the separate articles of this Dictionary. See AGREEMENT;

APPORTIONMENT; APPROPRIATION; ASSENT; ASSIGNMENT;

ASSUMPSIT; ATTESTATION; BAILMENT; BARGAIN AND SALE;

BIDDER; BILATERAL CONTRACT; BILL OF EXCHANGE; BUYER;

COMMODATE; CONDITION; CONSENSUAL; CONJUNCTIVE; CONSUMMATION;

CONSTRUCTION; COVENANT; DEBT; DEED; DELEGATION;

DELIVERY; DISCHARGE OF A CONTRACT; DISJUNCTIVE; EQUITY

OF REDEMPTION; EXCHANGE; GUARANTY; IMPAIRING THE OBLIGATION

OF CONTRACTS; INSURANCE; INTEREST; INTERESTED CONTRACTS;

ITEM; MISREPRESENTATION; MORTGAGE; NEGOCIORUM GESTOR;

NOVATION; OBLIGATION; PACTUM CONSTITUTÆ PECUNIÆ;

PARTIES; PARTNERS; PARTNERSHIP; PAYMENT; PLEDGE;

PROMISE; PURCHASER; QUASI CONTRACTUS; REPRESENTATION;

SALE; SELLER; SETTLEMENT; SUBROGATION; TITLE. — Bouvier's Law Dictionary, 1889

Contract. An agreement between two or more persons which creates an obligation to do or not to do a particular thing. Its essentials are competent parties, subject matter, a legal consideration, mutuality of agreement, and mutuality of obligation. Lamoureux v. Burrillville Racing Ass'n, 91 R.I. 94, 161 A.2d 213, 215. Under U.C.C., term refers to total

legal obligation which results from parties' agreement as affected by the

Code. Section 1-201(11). As to sales, "contract" and "agreement" are limited to those relating to present or future sales of goods, and "contract for sale" includes both a present sale of goods and a contract to sell goods at a future time. U.C.C. § 2-106(1). The writing which contains the agreement of parties, with the terms and conditions, and which serves as a proof of the obligation. Contracts may be classified on several different methods, according to the element in them which is brought into prominence. The usual

classifications are as follows: Certain and hazardous. Certain contracts are those in

which the thing to be done is supposed to depend on the will of the party, or when, in the usual course of events, it must happen in the manner stipulated.

Hazardous contracts are those in which the performance of that which is one of its objects depends on an uncertain event. Commutative and independent. Commutative contracts are

those in which what is done, given, or promised by one party is considered as an equivalent to or in consideration of what is done, given, or promised by the other. Independent contracts are those in which the mutual

acts or promises have no relation to each other, either as equivalents or

as considerations. Conditional contract. An executory contract the performance of which depends upon a condition. It is not simply an executory contract, since the latter may be an absolute agreement to do or not to do something, but it is a contract whose very existence and performance depend upon a contingency. Consensual and real. Consensual contracts are such as

are founded upon and completed by the mere agreement of the contracting parties,

without any external formality or symbolic act to fix the obligation.

Real contracts are those in which it is necessary that there should be something more than mere consent, such as a loan of money, deposit or pledge, which, from

| Page 15 |

|

![]()

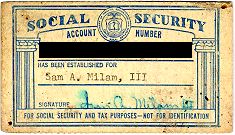

When the Social Security number became a mandatory form of identification, against my will and without my consent, I was compelled to either accept the

situation or to avoid the contract. I wasn't permitted any other options.

When the Social Security number became a mandatory form of identification, against my will and without my consent, I was compelled to either accept the

situation or to avoid the contract. I wasn't permitted any other options.